July 24, 2018

Testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The China Challenge, Part I: Economic Coercion as Statecraft

A video of the entire hearing is available online.

Submitted Written Testimony

I. OVERALL ASSESSMENT

Chairman Gardner, Ranking Member Markey, distinguished members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to discuss a topic of vital importance to the United States. Before delving into the specifics of Chinese economic coercion, I want to begin with four topline observations on the current state of the U.S.-China competition:

- The United States and China are now locked in a high-stakes geopolitical competition. How this competition evolves will determine the rules, norms, and institutions that govern international relations in the coming decades, as well as the level of peace and prosperity for the United States. There is no more consequential issue today in U.S. foreign policy.

- The United States, on balance, is losing this competition in ways that increase the likelihood not just of the erosion of U.S. power, but also the rise of an illiberal Chinese sphere of influence in Asia and beyond. If current trends continue, Asia will see a future that is less democratic, less open to U.S. trade and investment, more hostile to U.S. alliances and military presence, and more often dictated by raw Chinese power rather than mutually-agreed upon standards of behavior. To avoid these outcomes, the central aims of U.S. strategy in the near-term should be to enhance U.S. competitiveness and prevent China from consolidating an illiberal sphere of influence.

- The U.S. government has failed to approach this competition with anything approximating its importance for the country’s future. Much of Washington remains distracted and unfocused on the China challenge. The Trump administration sounded some of the right notes in its first National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy, but many of its foreign and domestic policies do not reflect a government committed to projecting or sustaining power and leadership in Asia and the world. On balance, I would characterize the Trump administration’s China policy as confrontational without being competitive.

- Despite current trends, the United States can still prevent the growth of an illiberal order in Asia and internationally. Washington’s ability to muster the necessary strategy, attention, and resources will go a long way in determining the character of international politics in the 21st century. The foundations of American power are strong, and the United States can successfully defend and advance its interests if only Washington can manage to pursue the right set of policies.

II. THE PHENOMENON OF CHINESE ECONOMIC COERCION

Mr. Chairman, I look forward to a broader discussion this afternoon on the wide-ranging question of China’s economic statecraft—including its Belt and Road strategy, its ambitious industrial policy, and its continued use of unfair and illegal trade and investment practices—but for the purposes of my opening statement today, I’m going to focus on the increasingly common and consequential phenomenon of Chinese economic coercion.

Economic coercion has become a fundamental part of Chinese economic statecraft and has had a chilling demonstration effect on the world. If left unchecked and unanswered, the shadow of Chinese coercion will continue to undermine U.S. interests not just in terms of immediate economic costs and changes in behavior, but more profoundly through a future deterrent effect. Facing the specter of economic punishments from Beijing, countries and companies are increasingly wary of standing up to Chinese illiberalism and revisionism, and several U.S. allies and partners are less willing to cooperate with the United States on certain diplomatic, economic, and security matters. We already see these damaging effects in a variety of regions and forums—in the South China Sea and ASEAN; on human rights, including in Europe; and even in the United States with U.S. companies, universities, think tanks, and state and local officials reluctant to speak truth to Chinese power. If the United States is going to rise to the China challenge, Washington will have to find a way to blunt this particularly pernicious element of China’s toolkit.

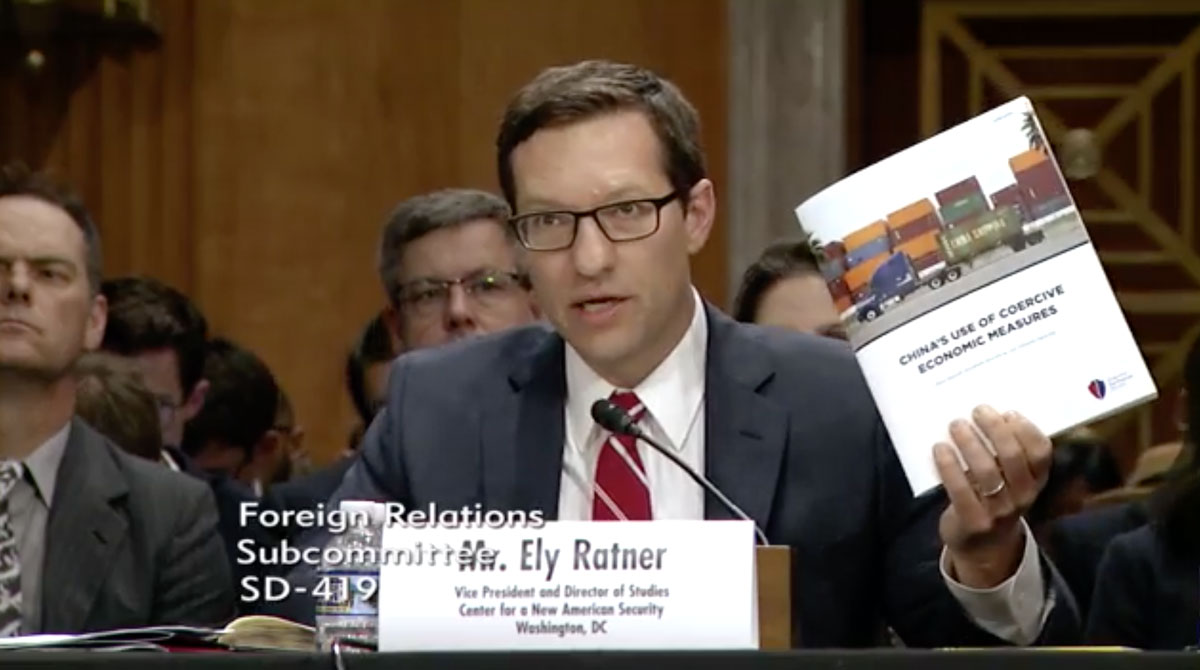

In June of this year, a team at the Center for a New American Security, the bipartisan national security–focused think tank where I work, published a landmark study on China’s use of economic coercion.1 I would encourage Members and their staff to read the report in full. The report defined economic coercion as the use, or threatened or latent use, of economic punishment for foreign policy and domestic political ends. To achieve such aims, China has used a vast array of coercive economic tools, including import restrictions, popular boycotts, pressure on specific companies, export restrictions, limits on Chinese tourism, investment restrictions, and targeted financial measures.

Although Beijing has employed these tactics primarily over sovereignty disputes and other particularly sensitive areas for the Communist Party, the set of issues that evoke Chinese coercion is growing and the tools are being deployed more frequently. This reflects China’s expanding economic and security interests around the world, greater coercive power enabled by its burgeoning economic clout, and Communist Party Chairman Xi Jinping’s more assertive, ideological, and revisionist approach to international affairs. At times, this international bullying is intended primarily for China’s domestic audiences, seeking to demonstrate the power and nationalism of the Communist Party.

A series of incidents over the last decade have illuminated the manner and circumstances in which Beijing uses economic coercion: Banning the export of rare earth minerals to Japan in 2010 during a clash over the disputed Senkaku Islands; freezing imports of Norwegian salmon after Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010; restricting imports from and tourists to the Philippines during a standoff over Scarborough Reef in the South China Sea in 2012; initiating popular boycotts and placing import and tourism restrictions against South Korea following the deployment of a U.S. missile defense system in 2016 and 2017; and imposing restrictions on imports from Mongolia after a visit by the Dalai Lama in 2016. The message has been clear: Don’t oppose Chinese revisionism in Asia, and don’t question the Communist Party’s worsening authoritarianism.

Over the last year, China has also attempted to coerce large Western companies into toeing Beijing’s line on Taiwan and Tibet. For example, China has been pressing international airlines to stop listing Taiwan as a separate country on their websites. And in February of this year, Mercedes Benz was compelled to apologize to China for quoting the Dalai Lama on a corporate social media account.

Chinese economic coercion differs in notable ways from U.S. economic coercion. Beijing has largely used informal and extra-legal measures, providing deniability and the flexibility to escalate and de-escalate at will. Moreover, as should be clear from the examples above, China is often using its newfound power and influence to advance narrow national and regime “core” interests, rather than to uphold and enforce international rules and norms. Beijing was content to sit quietly when Russia invaded Crimea, but has lashed out with economic punishments when foreign leaders met with certain internationally-recognized religious leaders or Nobel Prize laureates.

It can be difficult to gauge the relative success of these actions. On the one hand, China’s bullying does have negative repercussions: publics resent the pressure and economic hardship, and governments have at times sought ways to reduce future vulnerabilities. It is my firm belief, however, that we should not overstate the downsides for China. Beijing is making steady progress at building a sphere of influence in Asia, even if in a manner that is two steps forward, one step back. Indeed, even when an individual Chinese coercive action has little immediate effect, Beijing can still succeed in sending a powerful deterrent message to other countries making clear that they could be next. It would be a considerable mistake to sit back and allow these practices to go unchecked under the assumption that they will eventually backfire for Beijing.

III. GUIDING PRINCIPLES

Blunting China’s economic coercion is a strategic imperative for the United States. As the United States embarks on addressing this problem, it should do so with the following tenets:

- The foundations of American power are strong: We should be approaching the China challenge from a position of confidence. Despite all the pessimism about American decline, the United States continues to possess the attributes that have sustained its international power and leadership for decades. Our people, demography, geography, abundant energy resources, dynamic private sector, powerful alliances and partnerships, leading universities, democratic values, and innovative spirit give us everything we need to succeed if only we’re willing to get in the game.

- Rising to the China challenge is ultimately about us, not them: Since the end of the Cold War, U.S. policy toward China has sought to open its society and economy, while also encouraging it to become a responsible member of the international community. Instead, we find ourselves today confronting an increasingly illiberal, authoritarian, and revisionist power,2 and we should expect that China will continue heading in this direction (at least) as long as Xi Jinping is in charge. It is therefore no longer viable for the United States to predicate its strategy on changing China. Rather, how the United States fares in its strategic competition with China will ultimately depend on our own competitiveness, and we should be bolstering our own national strength and influence to gear up for this challenge.3 In short, even as we strengthen our defenses against China’s predatory economic practices, our China strategy should be focused on enhancing American competitiveness.

- Tariffs should not be the principal economic policy tool against China: U.S. tariffs raise prices on American consumers and businesses, invite retaliation, and are unlikely to lead to significant changes in China’s economic policies. Although limited tariffs are appropriate under certain circumstances, a better strategy would put more weight on a combination of high-standard multilateral rulemaking, investment restrictions, export controls, targeted public diplomacy, sanctions against Chinese companies guilty of stealing U.S. technology, investments in U.S. domestic competitiveness, regulations that encourage supply chain resilience and diversification, and closer coordination with allies and partners.

- We need a comprehensive China strategy across all domains of the competition: Regardless of the specific topic—Chinese economic coercion, human rights, or the South China Sea—the United States needs a comprehensive strategy that enhances U.S. competitiveness across all domains of the competition, including military, economics, diplomacy, ideology, technology, and information.4 It would be a mistake to approach our China policy as siloed and tactical responses to particular problems. Succeeding on any individual issue will require strength and skill across all areas of the competition.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CONGRESS

- Congress should hold hearings to re-examine the costs and benefits of rejoining the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

Rejoining TPP (now the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership or CPTPP) is the single most important thing the United States can do to advance its economic position in Asia, and to erode the effectiveness of China’s economic coercion. Joining a high-standard trade and investment regime will incentivize companies, including in the United States, to diversify their supply chains away from China, thereby lowering their dependence on and vulnerability to Beijing. Returning to a multilateral trade mechanism will also renew confidence in the credibility and commitment of the United States, while leaving China as an outlier as long as it pursues a state-led mercantilist model. The politics of this are obviously difficult right now in the United States, but both political parties need to find a way back to the deal. By not joining and stewarding an agreement with strong U.S. buy-in and protections, the United States is inviting continued Chinese economic coercion and, ultimately, Chinese dominance of Asia. - Congress should constrain the ability of the Trump administration to levy tariffs against U.S. allies and partners on national security grounds.

The United States should be working with—not alienating—allies and partners to address the China challenge, including sharing information on Chinese activities, coordinating on trade and investment restrictions, and rerouting global supply chains. It will be exceedingly difficult to address China’s coercive, unfair, and illegal trade and investment practices on our own. It was a mistake to lead with Section 232 tariffs on some of our closest allies, and similarly misguided to threaten auto tariffs against the European Union or withdrawal from NAFTA or KORUS. Instead, the United States needs an international economic strategy that differentiates between allies and strategic competitors. Congress should therefore set limits on the Trump administration’s ability to levy damaging tariffs on close U.S. allies and partners on specious national security grounds.5 - Congress should play an active oversight role on U.S. economic policy toward China by mandating that the administration produce a National Economic Security Strategy.

The U.S. government is not institutionally configured to deal with the China economic challenge. The issue of economic coercion, in particular, lacks a natural institutional home in the U.S. government. This dearth of U.S. government coordination invites further Chinese coercion and increases the likelihood that U.S. companies will buckle to China’s demands. Congress should use its oversight authority to urge the U.S. government to organize institutionally for the China economic challenge, including by passing proposed bipartisan legislation requiring the administration to publish a National Economic Security Strategy. - Congress should focus on enhancing American competitiveness by continuing to support increases in funding for basic research, formulating strategic immigration and visa policies, and investing in education, among other priorities.

Ensuring America’s continued economic strength and technological leadership is vital to reducing U.S. vulnerability to Chinese economic coercion.6 The U.S. government should therefore continue its long tradition of providing seed funding for critical technological breakthroughs. Additional domestic policies focused on enhancing American competitiveness will be critical to the strategic competition with China, including responsible fiscal policies, strategic immigration and visa policies, skills retraining for workers adversely affected by China’s predatory economic policies, emphasis on improving STEM education, and efforts to build a bipartisan consensus on the China challenge. - Congress should explore reconstituting a 21st-century version of the U.S. Information Agency.

The United States should revive its ability to engage in information operations and strategic messaging, which have not featured prominently in U.S. China policy for decades. The goal should be to provide a counterpoint to the billions of dollars China spends each year in propaganda to sell a vision of its own ascendancy and benevolence, alongside U.S. decline and depravity. The resulting perceptions of the inevitability of China’s rise and of future dependence on China have reinforced Beijing’s coercive toolkit. More U.S. media and information platforms could provide a degree of level setting about the facts and fictions of China’s power, expound the strengths of the United States, and cast a more skeptical shadow on certain expressions of Chinese influence, including its governing model, its ideological assertions, and the overall strength of its economy. U.S. information operations could also highlight Xi Jinping’s deep unpopularity around the world, as well as his mismanagement of China’s economy and failure to deliver on much-needed economic reforms.7 If creating a new institution like the U.S. Information Agency is not feasible, the U.S. government will still need more modern and sophisticated information dissemination tools. - Congress should increase funding for the Broadcasting Board of Governors to augment China-related content in Asia and beyond.

Current efforts to enhance U.S. government broadcasting and information operations in response to Russian disinformation campaigns should be expanded to develop more China-related content in strategically significant countries. A larger budget would allow Radio Free Asia to bolster its regional offices and employ more journalists throughout Asia to report on China’s activities of concern, including those related to the Belt and Road strategy. More resources for U.S. strategic messaging could also help U.S. entities to operate with greater sophistication on China’s own social media platforms, such as WeChat. Alternatively, failing to augment U.S. resources in the information space will make it much more difficult to succeed in other areas of the competition. - Congress should provide resources and direct the Defense Department to develop the means to circumvent China’s “Great Firewall” and make it easier for Chinese citizens to access the global Internet.

It will be important at times for the United States to be able to communicate directly with the Chinese people. The U.S. government should therefore invest in developing and deploying the technologies necessary to circumvent authoritarian firewalls, including in China. This would involve both developing cyber capabilities to disrupt China’s censorship tools, as well as finding new ways for citizens inside China to access a free and open Internet. - Congress should reinforce the Trump administration’s public reproach of China’s economic coercion by passing sense of the Senate resolutions criticizing China’s actions.

It is critical for the U.S. government to publicize and criticize Chinese economic coercion. If the United States remains silent during incidents of Chinese economic coercion, it is unlikely that others will be brave enough to stand up. Public statements by the Trump administration that highlight and diminish China’s actions in this area—including labeling China’s bullying “Orwellian nonsense”—is good policy. Official U.S. statements should also show support for targets of Chinese coercion. Congress has a role to play in naming and shaming acts of Chinese coercion, supporting U.S. allies and partners, while also holding private companies publicly accountable if they are compromising U.S. values and interests for commercial gain. - Congress should task the Congressional Research Service with publishing a regular report on Chinese economic coercion that outlines the incidents, costs, and policy tools used by Beijing.

As part of a broader public diplomacy campaign, the United States government should make available data on Beijing’s coercive measures to highlight the tools, methods, and consequences of Chinese economic coercion, limit Beijing’s plausible deniability, and facilitate further study by outside experts. - Congress should support the economic pillars of the Trump administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy by passing the BUILD Act, reviving the Export-Import Bank, and increasing foreign assistance in strategically significant sub-regions.

Bolstering U.S. economic competitiveness in the Indo-Pacific will require additional resources. Beyond simply criticizing China’s predatory policies, it is vital for the United States to offer concrete alternatives to China’s economic statecraft. Although the Trump administration has been slow to develop its strategy for a “free and open Indo-Pacific,” certain elements of the policy are now coming into view. It will not be necessary (or possible) to match China dollar for dollar. Instead the Trump administration should—in concert with allies if possible—pursue discrete development projects that showcase attributes of transparency, good governance, skills transfer, debt sustainability, and environmental protections, all in contrast to China’s way of doing business. Trump administration officials at the working level should be commended for beginning to advance an economic agenda for Asia despite strong headwinds. The upcoming “Indo-Pacific Business Forum” on July 30 is a good start, and Members from both parties should attend and participate if possible. - Congress should pursue measures to support supply chain diversification and redundancy and consider a counter-coercion fund to compensate targets of Chinese economic coercion.

The United States can take proactive steps to reduce the salience of China’s coercive economic power. Building diversity and redundancy in critical supply chains, for instance, could help to limit China’s leverage over key nodes in the world economy. Congress can assist by considering regulatory changes that reduce incentives for companies to source critical inputs from China. The U.S. government should also study the feasibility of creating a funding vehicle—possibly in cooperation with other developed economies—to compensate, in real time, targets of Chinese economic coercion. - Congress should call upon Commerce, Treasury, and other departments and agencies to develop tools to retaliate against Chinese firms and the interests of relevant government officials.

The United States government needs more tools to retaliate against acts of Chinese economic coercion, thereby helping to deter and, if necessary, impose costs on Chinese companies and the political interests of relevant Chinese officials. As a result, Congress should call upon departments and agencies to come forward with proposals for additional retaliatory economic measures. Otherwise, there is little reason why Beijing will hesitate from bullying American firms. Areas for consideration should include U.S. anti-trust statutes, export controls, licensing requirements, and investment restrictions. When appropriate, Congress should also urge the Trump administration to employ Executive Order 13694, which provides authorities for sanctions against companies that have stolen intellectual property for commercial gain.

- Peter Harrell, Elizabeth Rosenberg, and Edoardo Saravalle, “China’s Use of Coercive Economic Measures,” Center for a New American Security, June 2018, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/chinas-use-of-coercive-economic-measures. ↩

- Kurt M. Campbell and Ely Ratner, “The China Reckoning,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2018, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2018-02-13/china-reckoning. ↩

- Daniel Kliman, Elizabeth Rosenberg, and Ely Ratner, “The China Challenge,” 2018 CNAS Annual Conference, June 21, 2018, https://www.cnas.org/publications/commentary/the-china-challenge. ↩

- Ely Ratner, “Rising to the China Challenge,” Testimony before the House Armed Services Committee, February 15, 2018, https://www.cfr.org/report/rising-china-challenge. ↩

- Peter Harrell, “Congress must rein in White House economic national security powers,” The Hill, June 7, 2018, http://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/390958-congress-must-rein-in-white-house-economic-national-security-powers. ↩

- Elsa Kania, “China’s Threat to American Government and Private Sector Research and Innovation Leadership,” Testimony before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, July 19, 2018, https://www.cnas.org/publications/congressional-testimony/testimony-before-the-house-permanent-select-committee-on-intelligence. ↩

- This would not require the use of disinformation. For example, a recent Pew Research Center poll found that only 28 percent of respondents around the world had confidence in Xi “to do the right thing regarding world affairs.” (http://www.pewglobal.org/2017/06/26/u-s-image-suffers-as-publics-around-world-question-trumps-leadership/#trump-putin-and-xi-all-unpopular-merkel-gets-highest-marks.) Similarly, recent analysis by the Rhodium Group and Asia Society Policy Institute on the pace of Chinese economic reforms found that, “fourth quarter 2017 indicators continued to diverge from official reports: fundamental reforms are lagging while stated growth never seems to change. This does not make good sense, statistically or logically. We see eight of our ten policy assessments in neutral or negative territory.” (https://aspi.gistapp.com/china-dashboard/.) ↩

More from CNAS

-

The Financing of WMD Proliferation (JCE TEST)

Reports

The proliferation of weapons of mass destruction is a critical threat facing the international community. Numerous United Nations Security Council Resolutions (UNSCRs) place b...

By Jonathan Brewer

-

Leverage the new US International Development Finance Corporation to compete with China

Commentary

The United States has a unique opportunity to up its game in the global economic competition with China. In early October, even as Democrats and Republicans in the Senate enga...

By Daniel Kliman

-

On GPS: The future of US-China relations

Video

Former Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Kurt Campbell breaks down the factions and relationships shaping US-China relations. View the full vide...

By Kurt Campbell

-

Assessing America's Indo-Pacific Budget Shortfall

Commentary

Budgets are policy in Washington. Setting new trends in Pentagon and State Department funding is a tall order, so when they do emerge, they are the strongest indication of a g...

By Eric Sayers